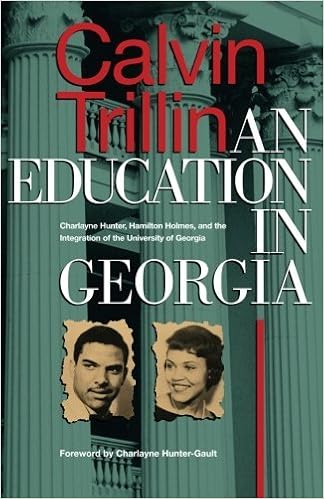

Part of a campus read at UGA this month, this work recounts the integration of the university largely from the point of view of the two first African American students to attend--Charlayne Hunter, Hamilton Holmes, and Margaret Early. Each represent different tacts and backgrounds taken in the fight for equal rights, and each experienced the events in different ways reflective of those tacts and backgrounds.

Early was a graduate student, so her experience was in some ways different from that of Hunger and Holmes, who tend to get more attention in the book (and, I find, in general). Hunter and Holmes went to the same high school, and both started off college somewhere else because of bogus rejections from UGA--Hunter went to Wayne State, Holmes to Morehouse.

Once accepted at UGA, Hunter lived on campus, while Holmes lived at a family's house. Holmes came from a family who had long been part of the civil rights movement, and his decision to apply and attend seemed a much more conscious (and family motivated) choice with regard to furthering that agenda. Hunter largely stayed on campus, while Holmes went home to Atlanta each weekend. Holmes took his studies very seriously; Hunter did not seem as focused on study. As such, Holmes excelled at the school but had a much less social experience; Hunter became more integrated into the university's social fabric, such as she could (some students and most faculty appear to have treated her well, but those same students at times had to step away from friendships because of threats and pressure from their other white friends).

Attending the university launched both Hunter and Holmes into their eventual professional fields. Holmes notes that while he did not enjoy his UGA years, his attendance allowed him the opportunity to attend Emory Medical School, which would not have been the case had he stayed on at Morehouse. Hunter would go on to become a renowned journalist, which is how I knew of her growing up in California, as she was often on PBS. Hunter's experience, as portrayed in the book, seems to be more about just trying to be a full-fledged person rather than an emblem of civil rights, though the two go hand in hand, since being treated equal as a person was the goal of civil rights movement. At the end of the book, for example, we learn that she married a white guy, something that she didn't want played up in media--this was her life, her love, her relationship, not something to be strutted out for some political end. And yet, it's impossible to separate the two when forces from outside raise the issue.

Some of the most interesting parts of the book to me had to do with the other Black students, the ones who came slightly later. This is a point Holmes makes very strongly at a presentation he gives later: that if others don't come, his and Hunter's and Early's efforts are wasted, as they become mere tokens. And indeed, as Trillin brings out, few tried to follow up, at least in those early years. Those who did included some younger female coeds who were pushed into Hunter's room on campus--indeed, all the Black girls were pushed to live together and thus separately from other students. More interesting was the story of one young man who opted to live in the dorm, who took part in various extracurricular activities, and who began attending a white church in town. He seemed determined to live the typical college life--to some success and, as the book shows, to a degree of failure to. His is a story that I would like to hear about in more detail, but being sixth or so in the set of names of early integrators, he is not the focus of most people's attention.

No comments:

Post a Comment