Where has Lucia Berlin been all my life, and why am I just last year hearing about her? She was a Black Sparrow author, that great old Black Sparrow Press, a publisher whose construction paper covers I long adored. But when I worked in bookstores, we didn't carry Lucia Berlin. Berlin has a strong voice. Her writing is as if she is telling you stuff from a memoir. It seems real, and yet it is harrowing.

In "Dr. H. A. Moynihan" an El Paso girl is kept away from outdoors where the kids of the neighborhood play--kids who are "dirty," meaning from other countries and races. Instead, she labors in her grandfather's dental shop. And one day, her grandfather insists that she operate on his own teeth. The descriptions here are raw and dangerous. I was reminded of a story I read in a creative writing class, years ago, about a girl who goes to get her tongue pierced; I wonder what ever happened to that young author?

The title story is a moving piece about a widow who takes up cleaning homes to support her four kids after her husband's death. There's a coolness of tone and a concreteness of language that makes Berlin's stories work so well. A piece like this could easily be maudlin. Instead, we get advice about cleaning homes and interspersed we're made to understand how much the wife has come to miss this man she loved.

Similarly well-placed language is used in the short-short "The Jockey," but Berlin really shines when she opens things up a bit, gives herself a little more room, as she does in "El Tim," the tale of a young non-Catholic teacher in a Catholic school forced to take on a juvenile delinquent in her class. Here, we watch a battle of wills unfold that is gripping. This is the stuff from which novels and movies could be made. What Berlin does here, however, is subtle--it's no over the top teacher baiting. It's just a run-of-the-mill change of tone in the classroom, much as such small changes can put an unnamed awkwardness on our own lives.

"Point of View" is metafiction, asking us to think about why we consider third-person narratives about the mundane to be consequential versus first-person narratives about the same. It was an interesting exercise in thinking about fiction and fiction writing.

"Her First Detox" is a scary tale about a woman's first trip to a detox center. It isn't the trip itself that is scary. There, she mostly tries to fit in among the other drunks and does a fairly good job. It's the title that is scary--"first"--suggesting a long, depressing road that is to follow.

"Phantom Pain" focuses on a woman's visits to her aging dad, who is slowly losing his mind and becoming someone even colder and more bitter than before. The daughter just wants some kind of reassurance that she's loved.

"Emergency Room Notebook, 1977" is an odd piece insofar as it has the real feel of a notebook. It's more a set of notes about the people and the work than a full-fledged story. But it also demonstrates what makes Berlin's stories so compelling, for those portraits are enough to keep one amused and wanting more. That more arrives in "Temp Perdu," which takes the same setting and tells a story--of a woman working at such a room and thinking back on the love affair of her life. What works here is the voice, the attitude--this is a woman who hates the hospital's clients but who knows also how much she can get away with in terms of not working. Great line, one nurse to another: "That's neat--you still think of love at your age." It says loads about both characters.

"Toda Luna, Todo Ano" tells of a widow vacationing in Mexico, trying to adapt, still, after three years to life alone. This is a longer piece, and the fuller-fledged portraits work well to ensure our connection to the story. The woman leaves her easy estate and goes to live among a set of clam divers (reminding me of Steinbeck's The Pearl). Subtly, she falls for one of the men, and yet both know that it's just a momentary thing, ending with the summer.

"Good and Bad" is about a girl in Catholic school whose American teacher of English and American history draws her away from class and into her own political concerns with the poor people of Chile. The girl has no interest in this, being from the upper class. It's fun to watch the American lecture the girl on the need to be active in one's community and about the meaning of life, even while the other snidely rejects all the high-minded thinking. The story's ending makes things a bit more personal and sad.

"Melina" is a great tale about a woman who has a certain effect on men--and on women. There do certainly seem to be people like this, people who draw others into their orbit just by being. You want to be near them, want to spend time with them. They're that charismatic, that wonderful. But often, such people are less tied to the others who find them so fascinating. Still, you are happy just for the amount of time you've been handed by this person, the blessing of their presence. So Melina boinks one man, marries another (who leaves her when she gets pregnant, since it's not his baby, but then begs to be allowed to return), and has an affair with yet another when the husband is gone (the affair being the great event of this other man's life). Years later, the narrator meets the woman at a party. She feels a certain draw toward her but also a certain jealousy, for she wishes on some level that a man could be drawn to her the same way. This causes her to do something she regrets.

The next several pieces are really short. "Unmanageable" is about an alcoholic mom getting ready for the morning by trying to get enough to drink so that she can function. "Electric Car, El Paso" is about a ride in such among a set of women who quote scripture to one another and try to guess the book, chapter, and verse. "Sex Appeal" is about an eighteen-year-old woman's attempt to get a date with a movie star--and about the young eleven-year-old cousin who helps her but who is the actual object of the movie star's perverse interest. "Teenage Punk" is about a mom who spends alone time with the drugged-out friend of her oldest son. "Step" involves a set of detox residents watching a welterweight fight with Sugar Ray Leonard.

"Strays" involves more detox--this time, it's a methadone clinic just as such treatments were catching on. Folks are forced to go there, forced out of their usual drug and drink regimen, but the setting is still derelict. There must be hidden anger in them all--trying to root out the trouble via psychology. They make up stories. They are angry at dogs that get fed. One night, the dogs get it--killed, gruesomely. Somehow, all this fits together, this feeling of a dead end that keeps getting deader.

In "Grief" two women hypothesize on the lives of two other women they observe. And they we get the story of those two other women. This was an interesting way to tell a tale, one I'd like one day to return to--making up stories about others. But it's also a story of the two women, how one in the midst of sickness grows stronger and how the other falls back into her old crutch.

In "Bluebonnets" a fifty-something woman goes out to visit a stranger, a man she's corresponded with and whose book she translated. The man lives out in the woods, like some Thoreauvian recluse. It seems ideal and beautiful, but as the visit wears on, it becomes clear why this man is a loner.

"Dear Conchi" is one of my favorites in the collection. I'm not usually a fan of expostulatory fiction, but in this case, the letters work. They're all from a girl writing to her friend Conchi, writing about her time going to school in the United States. An American citizen who grew up in Chile, she is learning the ways of a new country that is actually her own. Much of the story revolves around her interest in two men--one an intellectual and the other an anti-intellectual. The latter is also Mexican, which brings consternation to others at the school and to her own parents. As the story unwinds, this consternation begins to play a central role in the events that unfold and the eventual sad denouement.

Many of the stories following focus on Sally and her sister, the characters in "Grief." Sally has cancer; her sister, Carlotta, is/was an alcoholic. They had an upbringing with an alcoholic mom and a strict father who traveled around for work. This colors their lives; it is only now, as Sally's life is ending, that the sisters have made peace with their parents and with each other. In "Fool to Cry" Sally's sister goes to meet an old flame and comes to understand that the past can't be reclaimed. "Panteon de Dolores" recounts the sisters' mother's alcoholism and the father's travel and strictness. "So Long" recounts Carlotta's wild life, her marriages, and the affair that ran throughout them, the drugs and the drinking. Sally, by contrast, has lived by the book: one husband, a politician. Much of Carlotta's troubled life comes from her affair with Max, a heroin addict with whom she runs off.

"Mourning" focuses on a cleaning woman--one who goes to homes of the recently deceased. In this tale, two siblings argue over which things they want and which things to donate to their church. The cleaning woman notes how sad it is in either case--where families don't want anything or where they fight over what's left. Either way, our life's accumulation is cleared out in a couple of hours.

In "A Love Affair," a woman who has to cover for a coworker's affair. The coworker is happily married--in fact, happy about everything. The affair seems to be some way to satisfy others or to make her husband jealous or . . . Either way, it takes its toll not just on the husband but also on the coworker/friend, who has to rearrange her life and cover for the cheater.

"Let Me See You Smile" is another story about Carlotta, but this tale is told from the point of view of her lawyer. She gets in trouble with the law, defending some underage kids at the airport, friends of her children, one of whom (seventeen) she is having a relationship with. The gist of it is that the police report adds crimes and uses loaded language--enough that the lawyer can easily get them off. But the lawyer too is transformed. He finds that he likes Carlotta and Jessie and the rest of the family and goes to hang with them each Friday, even as his wife grows more distant. When the case is over and the professional relationship ends, which means that technically the relationship ends, there is a kind of mourning.

"Carmen" is one of the most harrowing stories in the book. It recounts a pregnant woman's journey across the border to score heroin for her husband and the impending pregnancy while the one she loves is high on drugs. It's the sort of deadpan among such travesties that makes these stories often shine and shock.

"Silence" is another story about Carlotta, this time as a little girl--it's a narrative of her one real friendship and how she loses it. But like so many of the stories, its real power comes from the gut punch that happens when we know what is to happen to Carlotta later in her life.

Another one of my favorites is the extremely powerful "Mojito," which made me cry. It's about a Mexican woman who marries an American, who is then sent to prison. Forced to live with his no-good relatives, to give up what assistance she receives to them, before being eventually kicked out to the street, she struggles each day to figure out how to provide for the baby she's had, a baby she knows nothing about raising. The piece is told from her point of view and from the point of view of the doctors she goes to visit. The latter seems almost unnecessary until the end, when a first-person point-of-view would likely not work--Berlin makes the right choice here by putting a certain distance between us and the events in the woman's life.

"502" rehearses the life of a drunk--but it focuses especially on her relationship with one officer Wong, and most especially on their first interaction, one in which the drunk's car rolls down the hill without her, crashing into another vehicle and how she gets out of trouble via the other neighborhood drunks, a sort of community in which the patrons stick up for one another.

In "Here It Is Saturday," a group of convicts share time together in a creative writing group. As with so many creative writing groups, the people inside it grow very close to one another, given how vulnerable it is to expose one's writing. One star pupil outshines them all, however. But as it is some communities, one can't have someone becoming an actual success.

"B.F. and Me" is about a repairman and an old sickly lady. The former comes to fix the woman's bathroom floor, but like all such men, proves unreliable. Still, he's sexy. The idea of sexiness is turned around here quite a bit, relying mostly on voice rather than our usual expectations.

"Wait a Minute" returns readers to the character of Sally, this time as the cancer that assailed her body finally takes her life. And "Homing" focuses on another older lady, this one noticing how blackbirds come to her backyard, forcing her to think about all the other things she missed in her life and to consider what it means to have regrets: each opportunity not taken is a different opportunity that would have been lost. No use, in other words, wishing to have made other choices. These latter stories, we get the sense, are about Berlin looking back on her own life.

Monday, March 13, 2017

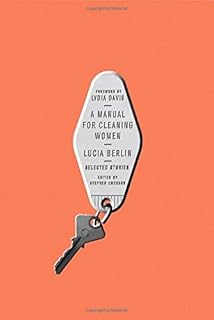

On "A Manual for Cleaning Women" by Lucia Berlin *****

Labels:

Books,

Collections,

Five-Star Collections,

Lucia Berlin

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Wow what a great blog, i really enjoyed reading this, good luck in your work. Cleaners Daphne AL

I really liked your Information. Keep up the good work. Gordon Engle

Post a Comment